How Much Does Risk Cost? 3 Real-Life Project Examples

By James T. Cicero and Rocco Gallo | Jan 24, 2019

Risk costs money. Design-assist is one way to avoid it. In this article, we show how.

“Why in the world would I want to spend more money on my project?”

It’s a great question. On most projects, clients are looking for ways to save money. They want to get the most value for their budget.

So when we talk about design-assist and suggest that clients invest more in preconstruction, they’re skeptical. They see dollar signs. They want to know that spending more money up front actually adds value to their projects.

That’s why, in this article, we share three real project examples where a discovery during construction led to an owner-paid change order on the project. (We’ve modified identifying elements as appropriate.)

We reveal what each unexpected issue cost the project. Then, we describe how design-assist could have helped the team discover the issue before it became a change order.

We think these examples will look familiar to anyone who’s worked in the AEC industry. They fall into territory known as the Spearin Gap.

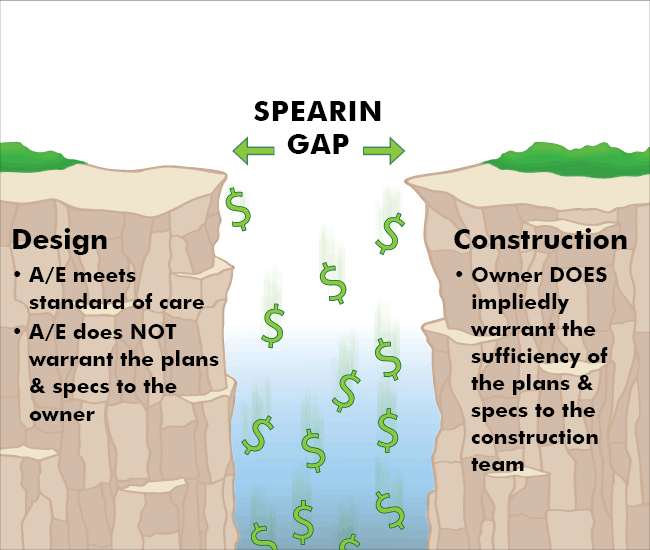

The Spearin Gap Is a Financial Risk for Owners

When a change falls in the Spearin Gap, the cost of the change ultimately belongs to the owner.

Without getting deep into legal jargon (this article is not legal advice), here’s an outline.

The design team and the construction team have different relationships with the owner.

When the design team designs a project, they are responsible to the owner for meeting the standard of care. The design team does not, however, warrant the plans and specifications to the owner. In other words, the drawings are not guaranteed to be perfect.

The owner, however, impliedly warrants the sufficiency of the plans and specifications to the construction team. The owner effectively guarantees that the drawings will be enough to do the job right. (See this article.)

As a result, when the design team has met the standard of care, and the construction team has met their obligations, then the owner is responsible for covering the costs of issues that arise.

Hence the gap.

During construction, the gap can widen with change orders that eat up the contingency (or eat into other projects). It can lead to delays that impact an owner’s business. Depending on the size and complexity of the project, the owner’s risk can be incredibly high.

For owners, the million-dollar question is, “How do I close that gap?”

We believe one powerful answer is design-assist. These examples illustrate why.

Example 1: Discovery of Dangerously Old Equipment Delays Projects and Adds Significant Cost

A client asked the design team to relocate an electrical feeder. The feeder was blocking a new construction project on a healthcare campus. The scope was simply to relocate the electrical line.

During construction, the contractors needed to shut off the electrical lines. They discovered that the medium voltage selector switches were 50 years old. This made them pause.

Before shutting off the switches, they contacted the manufacturer. The manufacturer said that the switches were beyond their life expectancy and may not function properly. The manufacturer could not guarantee that once the switches opened that they could reclose.

With this information, the contractor wasn’t going to risk shutting off the switches and causing a substantial, extended outage at the hospital.

As a result, the project suddenly included a large change order to replace the switches. The additional work delayed both this project and the project it was enabling.

Change Order to the Project

Approx. $200,000

Why Design-Assist Could Have Helped

- During design, one key task for design-assist contractors is to map out project constructability. The design-assist contractor would have accompanied engineer on site visits and flagged the switches for investigation. The contractor would have then looked into the switching sequence and investigated how the switches would operate.

- The design team would have been able to incorporate the switches into their initial design and estimates.

- Instead of getting caught in a scramble, the hospital would have known the cost and schedule implications up-front. This would have enabled them to adjust their budget, plans, and expectations in advance.

Example 2: Inaccurate As-Builts Lead to an Expensive Change

While designing electrical systems for an office renovation, the team needed to add a breaker to an electrical panel. The as-builts indicated that the panel was capable of having a breaker added.

During construction, the contractor opened the panel cover. They discovered that, while there was space in the panel, the buss bars (which the breaker would connect to) didn’t extend far enough to actually connect the additional breaker.

The discrepancy between the as-builts and field conditions resulted in a change order to augment the electrical gear. The task, which required a custom solution, took longer than originally anticipated. Plus, the team needed to schedule the shut-down so they didn’t disrupt the facility’s day-to-day operations.

Change Order to the Project

Approx. $30,000

Why Design-Assist Could Have Helped

- An electrical design-assist partner would have performed walk-throughs alongside the engineering team. They could have opened the panel cover (something engineers are not qualified to do) and performed field verifications.

- The engineers would have designed the panel modifications into the project. The bid and project schedule would have accounted for the modifications.

- Rather than being forced to pay for an add during construction, the owner and design team could have reduced cost elsewhere on the project to cover the modifications.

Example 3: Inoperable Ventilation Fan

During a higher education facility renovation, the construction team discovered that an existing attic ventilation fan was not operational.

During design, the design team had verified that the fan existed and appeared to be operational. Since the fan was controlled and not supposed to operate continuously, the design team wouldn’t have known it wasn’t functioning.

As a result, the team needed to replace the fan and add new controls during construction.

Change Order to the Project

$7,000

Why Design-Assist Could Have Helped

- The design team could have asked the design-assist contractor to operate the fan and verify its controls and capacity.

- When the design-assist contractor discovered the fan wasn’t working, the design team would have incorporated a new fan and controls into the initial design and estimate.

- If needed, the owner and design team could have reduced cost on the project elsewhere to cover the fan and controls.

Bonus Example: Design-Assist Team Creates a Path to Cost Savings

On a healthcare infrastructure project, the project team needed to extend fuel oil piping from the basement of one building to the roof of a neighboring building. It was a challenging task. The piping ran a distance of about 1,000 feet. It could take several possible routes, and each team member had different ideas about what would be best.

The mechanical contractor made the initial plan for the routing. Then, the architect, engineer, construction manager, and mechanical contractor all walked the proposed route. Together, they came up with a better route through the building.

Cost Avoided

$15,000 - $20,000

Why Design-Assist Helped

- All the relevant parties were “in the room.”

- Each party knew about different components related to the routing (previous building renovations, code implications, installation safety considerations, etc.).

- Collectively, they were able to develop the best routing for both the owner and the installation.

Conclusion

When an owner and project team have the right information at the right time, they can remove risk from a project.

In extreme cases, like the first example, design-assist might not rescue the project budget. In other cases, like the rest of our examples, design-assist would have helped the team maintain the budget, avoid costs, and find better solutions.

In all these cases, design-assist would have allowed more informed decision-making, fewer change orders, an accurate budget, and a realistic schedule.

That’s the power of design-assist.

Have your own Spearin Gap story? Share it in the comments. We promise to read every one.